Sometimes I come across educators who have questions and concerns about why they are asked to focus on "target learners" to inform their inquiries into their practice.

I have an issue with putting labels on people so I don't enjoy talking about "target learners" or "priority learners", in much the same vein of thinking as Alex Hotere-Barnes and Shelley Moore (among many others).

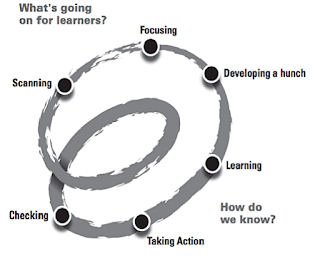

Spiral of Inquiry - Kaser & Halbert, http://noii.ca/

Aside from the fact that it would be largely impractical to do justice to the Scanning phase if we focused on a large group of learners, this post explains why it is best to focus on a small group of specific learners.

In a nutshell, here are the main reasons that we focus our Spirals of Inquiry Scanning and Checking on a small group of learners with learning (and teaching) challenges attached to them:

1. We have a moral imperative to investigate more deeply the reasons why we are unable to meet these learners' needs as well as we seem to be able to meet the needs of the rest. Equity should be our aim.

2. The very nature of Spirals of Inquiry requires us to find complex pedagogical and instructional problems to solve. This complexity lies in our successful and unsuccessful practices attached to those learners who are not experiencing as much success as others for whatever reasons.

3. Changes made in our teaching practices for a small group of learners will be embedded and sustained in our practice and will have an impact on all learners. We're not going to only use these new practices during the times we are with the few learners, we are going to make significant change that will impact on our learning and teaching as a whole. It may be that in the past, our inquiries have involved simple (and sometimes short-term) changes in practice targeted on a few learners, but in-depth teaching as inquiry should always seek to make deep and lasting change in practice for all learners.

If you really like to read - check out some further thinking below that expands on these points.

A moral imperative

The case for focusing on a small group of learners through Teaching as Inquiry in order to change teaching practice includes the following points and information from the BES on Teacher Professional Learning and Development - where the Inquiry and Knowledge-building Cycle was articulated in 2007. The whole point of Teaching as Inquiry is to solve instructional or pedagogical problems and improve learner outcomes. Instructional or pedagogical problems are related to those learners for whom school and learning is just not working. We focus on these learners as that is our moral imperative in education - to ensure that learning and school is working for ALL learners, not just most of them. Why would we not focus on these learners when considering how to change our practice? What would happen if we focused our attention on learners already doing well at the expense of learners who need us to change if they are to succeed? Engaging in Teaching as Inquiry effectively requires that we seek a wide range of evidence. We can't focus our energies on all learners if we are to do justice to quality, in-depth Scanning, Focusing and Hunchwork. I usually recommend that teachers prioritise learners who are not currently succeeding in school. They can then choose to add other learners to the mix (these could be learners who are achieving well yet are disengaged, or learners who are achieving well yet have social emotional issues that may be interfering with their potential to do better). The main point is, we have a moral duty as teachers and leaders to continue to seek answers to our most pressing problems that may be contributing to low achievement and/or serious disengagement in learning.

Change in teacher practice has a wide-ranging effect

Changes made in our teaching practice have an effect on all learners even though we remain predominantly focused on a smaller set of learners for the reasons above. We find through inquiry that instructional and pedagogical problems linked to a smaller set of learners are also impacting on a wider range of learners and therefore, the changes we make to address these problem practices will impact on all learners. As we change our practice, we don't simply change it for the times when we are working with one small group - we change our entire pedagogical and instructional approach to address the identified problem practices. Ultimately, teaching as inquiry is about teachers changing their practice - with depth and width. The changes are embedded and sustained and the new pedagogical and instructional approaches are grounded in strong research as well as adjusted to our specific contexts. Therefore, we know that what we choose to do to support the learners identified will also work for all other learners. We use the Checking phase to continually check in on all learners - using our regular processes for checking and perhaps some specific checking processes to see if we've made enough of a difference for the learners we focused on.

Professors Russell Bishop and Mere Berryman also completed a lot of research to show that what works for Māori will work for all learners - this is a similar concept and is worth exploring to better understand how effective pedagogies designed for specific groups of learners can work generally for all. The PDF below also provides more thinking and reading to build understandings of the interconnectedness of change in practice, evaluative capability and teacher interdependence and how the focused growth in these areas can impact widely.

Other resources and references that may be of use

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Report from the Medium Term Strategy Policy Division. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R. (2001). Changing Power Relations in Education: Kaupapa Māori Messages for Mainstream Institutions. In The Professional Practice of Teaching, 2nd ed., ed. C. McGee and D. Fraser. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R. and Glynn, T. (1999). Culture Counts: Changing Power Relations in Education. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Timperley, H. (2008). Teacher Professional Learning and Development. International Academy of Education Educational Practices Series, no. 18.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Comments